by Ken Hackman

My friend Doug Wood would have been a perfect subject for the Readers Digest column; “The Most Unforgettable Character I have ever met”.

My friend Doug Wood would have been a perfect subject for the Readers Digest column; “The Most Unforgettable Character I have ever met”.

A native Californian, he was born on December 4, 1922 in Long Beach, CA. His parents were Charles Orson Wood, a butcher, born in New York and Grace May Wood, nee Bridgford, a housewife born in Utah.

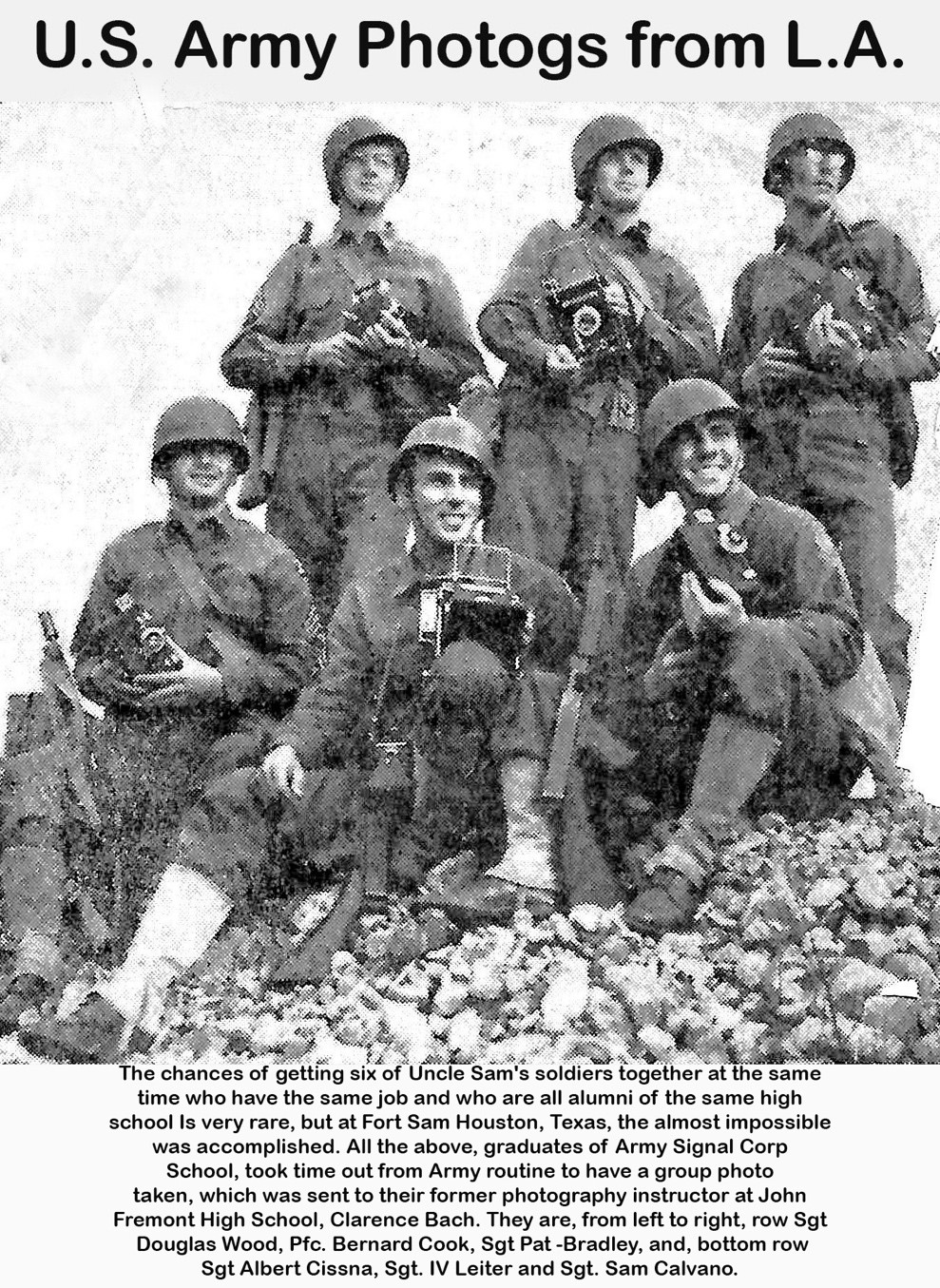

He attended John Fremont High School where he studied photography for three years under Clarence Bach who became renowned for the successes of his students, eight would later work for LIFE magazine and six friends and fellow students joined Doug in enlisting in 1942 in the U.S. Army, where he became a motion picture cameraman.

A mutual friend, retired Col Dale Boggie agreed. After Doug’s passing, he wrote:

Editor’s Note: I have excerpted Dale’s comments, identified with this font, for this PROFILE.

IN MEMORIAM *** GEORGE DOUGLAS “DOUG” WOOD***

Doug Wood was an amazing individual who led an equally amazing life. He had a knack to be at the right place at the right time, including how he happened to get into the photography business. He and a buddy decided to join the Army during WW II and went down to the recruiting station in Hollywood to enlist. Just then an Army Colonel came by looking for anyone with motion picture or photo experience. Doug said he did, which was embellished a little since he only had a camera and had developed and printed his own film. Regardless, the Colonel was suitably impressed and said he could take Doug in as a Staff Sergeant, give him a jeep and a driver and he would document combat actions of the Army. This sounded good to Doug, who promptly accepted, while his buddy went off to boot camp as a Private

Like many other American soldiers, he ended up in Normandy with the 165th Photographic Company: Here is one recollection transcribed from Doug’s handwritten note.

About 6 or 7 days after D-Day Norris, Katalia and our other camera crew came ashore with the jeeps and ¾ ton weapons carrier. Later on, we were sent to take everyone up to the north end of the beach to photograph Fort Ste. Marcouf near the town of the same name.

About 6 or 7 days after D-Day Norris, Katalia and our other camera crew came ashore with the jeeps and ¾ ton weapons carrier. Later on, we were sent to take everyone up to the north end of the beach to photograph Fort Ste. Marcouf near the town of the same name.

I told everyone that the road was cleared but everything else in town was mined and booby trapped. “Don’t Leave The Road”!

We left Norris and Katalia with the jeeps and walked to the Fort which was a complex of concrete bunkers and pillboxes to protect the coast from landings. (Part of the so-called West Wall)

While we were there, the other still man wasn’t doing anything, so he went back to the jeeps. Then he decided to walk. Thru the church yard (which was the town cemetery) Norris followed him as they were walking along the path. Norris stepped on a Schu landmine. The camera guy (no name comes to mind) and Katalia were so shocked (I guess) that they honked the horns on the jeeps.

We had heard the explosions, so we went right back. Norris was laying in the pathway for me by name to help him, so I real quick walked in and got him. When I got him back on the road near the jeep, I put him on the ground and gave him a couple of shots of morphine. (I still had some surrettes from D-Day). Then I put sulfa powder on his stumps. One leg was gone about half way to the knee with the top of the boot blown up his calf which was helping the bleeding. The other leg still had part of the heel bone and toes hanging on by skin on top of the foot.

I put him in the jeep and had Katalia hold his legs straight up and pinch the pressure points on back of his knees. Katalia was a complete wreck after that but I was too insensitive to that kind of problem. He had gotten sick while I worked on Bob. I wanted to get Bob to a medic or hospital, so I wasn’t thinking about Katalia’s problem.

We drove back down the road running parallel to beach and a Regt. of (I think) the 79th Div was coming north along the road and they were taking a break, resting alongside and on a seawall. I asked one of the guys where there was a medic? He pointed to a guy laying on the seawall and he was the regimental surgeon. I went up to him and said I have a hurt guy here that I need you to look at. He said, “I’m on a break”. I was so pissed that I got up real close and whispered to him that if he wasn’t off that wall and working on my guy, I’d shoot him. He jumped up and went over to the jeep, looked Norris over and said, “I’m going to hurt you son” and. Bob replied, “I’m already hurt Doc”. He wacked off Bob’s toes and tied the upper flap of skin back over the rest of the wound and put a pad on the backs of the knees pressure points and gave him another shot of morphine and we took him to a field hospital. The Maj. (Surgeon) apologized to me for not jumping up right away but thought I was from their outfit and they hadn’t had any casualties. I said I was sorry to have threatened to shoot him but was in a hurry. He laughed and said “It got me moving”.

After that whenever there was a loud noise, Katalia would drive us into a ditch. I told him he’d get us killed doing that case the engineers didn’t clear the edges of the roadways and there we lots of mines. I finally told Messina I had to get rid of him so lets have him transferred to CO. Hqs. Messina wouldn’t do it. Then one day Katalia left us with no wheels when we got back to the place where we had left him a mile or so behind the line we had to bum a ride back to the Div C.P.

I took off to the CO. CP and got either Smoody or Hawley to give us a replacement driver. He was the guy who got hurt in the bombing by our own guys on 25 July. ( I think it was a guy named Larry Hoffman.)

From there we went to an area facing the town of Mortain which was on a hillside, up high and the roads around there went to Avrranches. The Germans were attacking with 2 or 3 Panzer Div. trying to get the road cut to prevent us from taking the Brest Peninsula. That started about 1 Aug and it was 7 days before we got them stopped and took Mortain.

The next day we were photographing the Inf. attacking a hill they started moving up the hillside with the cannon company firing at the hilltop where the Germans were. We started photographing the cannon company. Then some P-47s arrived to bomb the Germans. The German AAA hit one guy, he turned towards our lines, rolled the plane on its side and dove out. The plane in a turn headed straight for us, it crashed a couple of fields before us but scared the shit out of everyone, especially me. That night we had to go back to the Div. C.P. to get more film and turn in what we had shot. Messina insisted that we do the captions and turn the film into the courier before we could eat or dig a hole. By then it was dark so Norbie and I slept, one on each of our jeep planning on rolling under the jeep if the Germans bombed us. Sure enough they came with Butterfly Bombs (cluster bombs) dropped in a canister that split open at 5000’ and spread the little bomblets which could be set for different times. They were loaded with split ¼” found pellets inside.

Norbie beat me to it and rolled under the jeep clear to my side and he wouldn’t move. I waited for a lull in the bombing and ran over and got in Rouse’s hole with him by then my shattered nerves took over and I was so scared my teeth were chattering and I couldn’t stop it. I remember trying to tell John I was sorry but I couldn’t help it. I got over it.

We then had a couple of easy days of moving down to Mortain. In the meantime, Messina got a chunk in his arm and wanted to go to the hospital. I finally got a medic to look at it and he told him to take his pills and go to the doctor in the morning cause they were all busy with serious injuries. I told him I had been hurt worse on K-Ration cans. (Just a few days prior to that Mauldin had drawn cartoon of Joe standing in front of the medic’s sick call table, with Purple Hearts on one side, aspirin on the other and the caption read “I’ll just take the aspirin”) I couldn’t resist pinning it up on his field desk. He insisted that I drive him to the hospital the next morning. He stayed two day. Then we moved to Mortain and with the rest I got calmed down and was okay after that.

In December 1944 and January 1945, the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes region of Europe was later described as the greatest single battle the U.S. Army ever fought.

This led to many adventures, one of which was related by General Eisenhower’s son John S.D. Eisenhower in his classic book The Battle of the Bulge (pages 428-429). Doug sent me a copy of the book and also filled me in on the way the incident happened. Doug, his driver and still photographer were out beyond the American front lines to photograph the linking up of the 1st and 3rd Armies who had been pushing the Germans back from their counter attack incursion, which began on December 16, 1944 and which was termed The Bulge.

Doug went to where lead elements of the 1st Army were, commanded by Colonel O’Farrell and told him he was there to photograph the link-up. Colonel O’Farrell didn’t know of any such link-up. So, Doug was a little disappointed and decided to get up on a hill to see the action. He could see down in a valley where the Germans were retreating but still firing back at the pursuing 1st Army units. Then a bunch of troops from a 3rd Army unit came up out of the woods behind him, soaking wet from having forded a river. They were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Foy, who was looking for anyone from the 1st Army.

Well Doug knew just where they were and volunteered to lead LtCol Foy to them. As they approached the tanks of the 1st Army, Doug yelled out, “Col. O’Farrell, there’s a Colonel from the 11th Armored, 3rd Army here to see you. Sir.” Colonel O’Farrell stuck his head out of a tank turret and was immediately recognized by LtCol Foy who hadn’t seen him since they had been stationed together at Fort Knox. And, so the Bulge was closed on January 16, 1945, facilitated by Staff Sergeant Douglas Wood, 165th Signal Photo Company.

Doug had an even more fascinating tale to tell. He and his crew were looking for combat action to film and were again, out in front of the line. They drove into a little town and found it all but deserted by the retreating Germans. A German soldier stepped out of a little house with his hands up wanting to surrender. Doug said okay, come forward, then asked if there were any more with him. The soldier said yes and pointed back toward the house. Doug went there to find 19 more young German soldiers. He told them to break up all their rifles, and then got a sack for them to put all their Luger pistols in – which Doug kept. He then had them form up and marched them up to the deserted town square, where he kept them until he could turn them over to an Army unit which arrived.

Doug said that those Luger pistols were great trading items and he managed to keep one and get it home. He showed it to me, and it was in great shape and fully functional. It is a priceless memento along with a picture his still photographer took of Doug marching the troop of German soldiers, armed only with his motion picture camera.

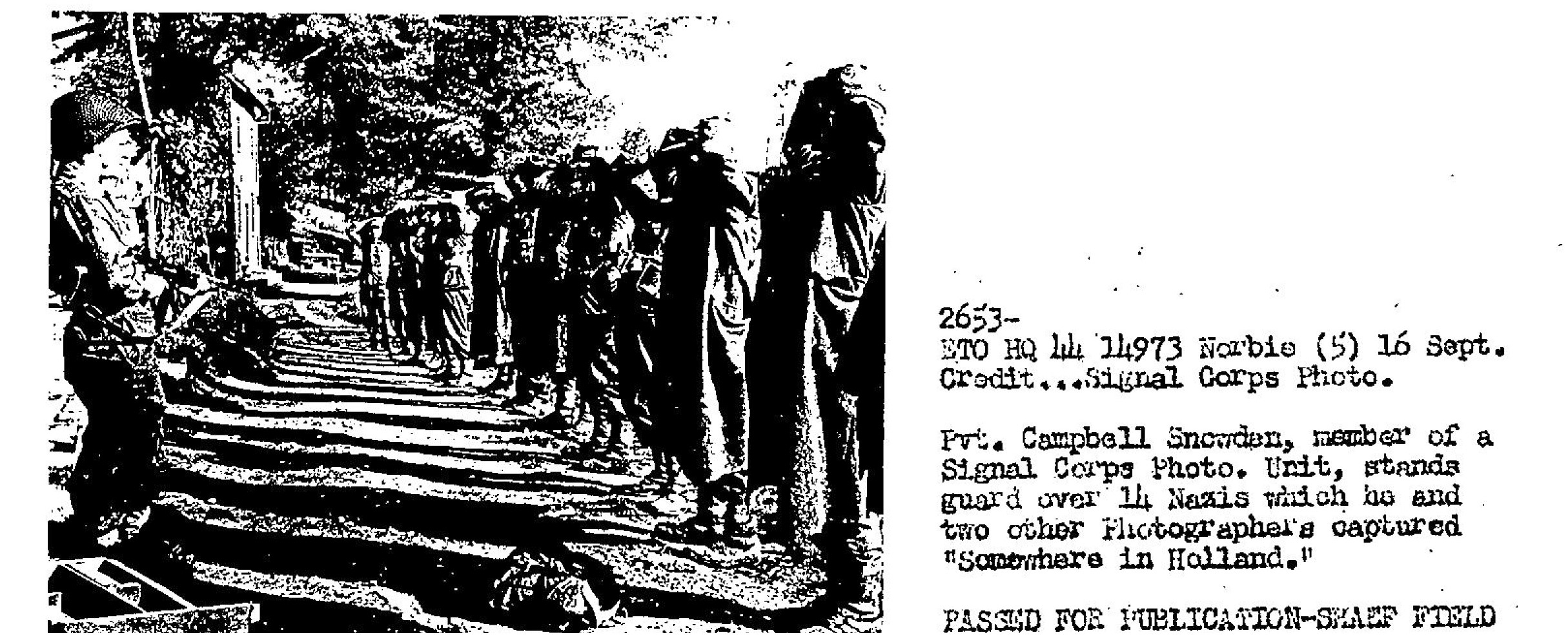

Another memorable encounter for Doug, the still photographer Sgt. William Norby and driver, Pvt. Campbell Snowden was recounted in this letter from a Dutch family about the liberation of their village by three American soldiers.

Eygelshoven, Nov 5, 1945. Holland

Dear Mrs. Snowden,

You will be quite surprised to hear from an unknown Dutch family. The question is this: On September 20, 1944 we were liberated from the German oppression by the first American soldier we ever saw and that was Campbell Snowden. He came to our coal-mine and then with some mining-engineers to our house while the German shells were exploding everywhere, and we were in the shelter. We were awfully grateful to him (and of course to the whole U.S. Army) for liberating us and we welcomed him with our last bottle of champagne and the singing (for the first time after 4 ½ years) of our national hymn. That evening he came back with two of his friends, Douglas Wood and William Norby, and we celebrated our liberation with them and all the mining engineers and their wives. The party lasted till 3 in the morning and we did not mind shells or guns or anything because we were so glad to be free again. After that we all went to bed and the three guys slept till 10 in the morning. During the evening, Father made a little speech to them to thank them and he gave “Shorty” a present (for he was the first one). It was a bronze little statue of a big boy, meaning America and he is helping a little girl (Holland). It was too big for Campbell to take with him and we promised to send it home after the war as soon as it was possible. The statue had been hidden in the earth, the Germans wanted to have all the copper and bronze.

But we never heard from Campbell, nor from his friends anymore. What became of them? Are they home already or what is it? We really hope to hear from you and if we can do something for you please write it then.

The Family Edixhoven,

Eygelshoven (z.l.) Holland. (Europe)

Letter was sent to: Mrs. Snowden, R#2 Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, U.S. America

As a result of this and other events, all three, Sgt Doug Wood, Sgt William Norbie and Pvt Campbell Snowden were awarded the Bronze Star Medal by Lt. Gen. Hodges, Commander, 1st U.S. Army.

During the war, Doug, photographed battles and campaigns in Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Rhineland and Central Europe. In addition to the Bronze Star he was awarded the European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, American Campaign Medal, Good Conduct Medal and 1 Bronze Service Arrowhead.

He was Honorably Discharged on 31 October 1945 at Fort MacArthur, California.

He along with many of his Army friends got jobs at Lookout Mountain Laboratory (LML), later named Lookout Mountain Air Force Station (LMAFS). Lookout was the single agency responsible for all the documentary photography coverage of the atomic bomb testing by the United States in the Pacific and the Nevada desert. Doug, as a cameraman and later as the Chief of Motion Picture, was involved in the documentation of the atomic tests conducted in the Pacific until the final atmospheric test, Operation Dominic in 1962.

After the war, Doug continued on in the photo business and was involved in the early tests of the atomic bomb. A whole chapter could be written on those days. I remember one of his stories where he was to witness and film an atomic bomb explosion. They were all given special goggles to wear to shield their eyes. When the countdown started Doug was still messing with his camera and grabbed for his goggles but couldn’t find them. So he just put his hand over his eyes. Even with his eyes closed and his hand covering them, he still clearly saw all the bones of his hand when the bomb went off.

Doug formal education was a High School Diploma, but he was the smartest, most intelligent problem solver I ever met. During the early space program, he was vital in the development of camera-bearing pods and placing them on F-4C Phantom fighters as noted in this McDonnel Air Scoop publication in February 1965.

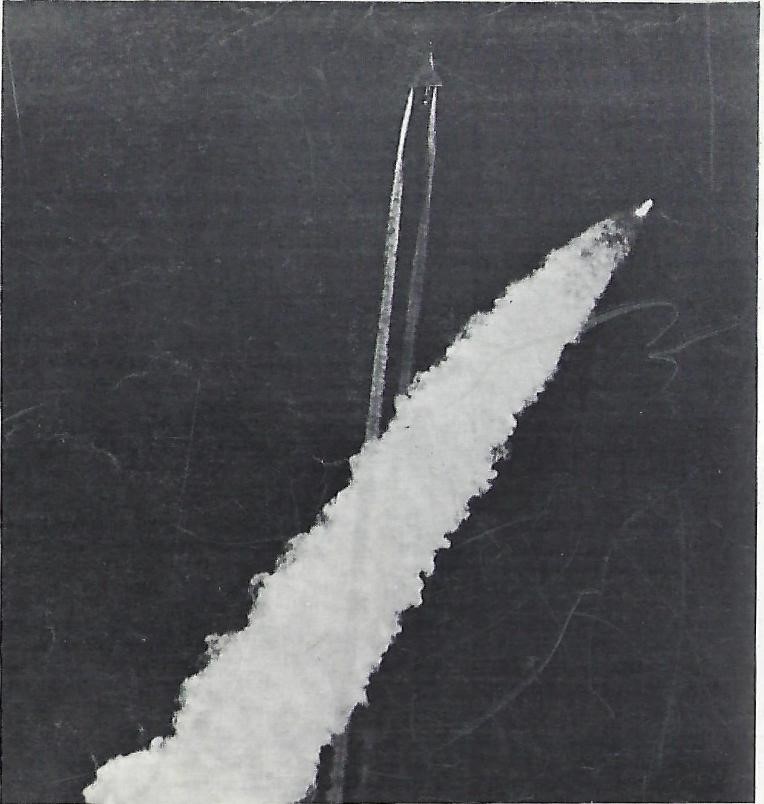

VAPOR TRAILS of a McDonnell F-4C Phantom form dramatic cross in sky with fiery contrail of the GT-2 ascent shortly after McDonnell-built Gemini Spacecraft No. 2 was launched from Cape Kennedy. The Phantom was one of two F-4C’s which tracked the Gemini and its Titan booster to capture high-altitude, air-to-air photos of the early part of the space mission.

Tactical Air Command Phantom F-4C’s from MacDill Air Force Base at Tampa tracked the GT-2 flight of Jan. 19 and obtained the first high-altitude, air-to-air motion pictures of the ascent of a McDonnell-built Gemini spacecraft.

As Gemini Spacecraft No. 2 and its Titan II booster climbed from the launch pad at Cape Kennedy, they were chased in ascent by two camera-bearing F-4C Phantoms. It was the first such photographic coverage of a Gemini mission. Plans are to similarly photograph the launches of future manned Gemini flights.

Phantoms From MacDill

The F-4C’s took off for the Gemini chase from Patrick Air Force Base near Cape Kennedy. The sonic booms of the F-4C mission reverberated throughout the entire Cape area. MacDill pilots who manned the planes were Lt. J. R. Petry, Capt. W. R. Seal, Capt. J. D. Musgrove and Capt. J. E. Fidler.

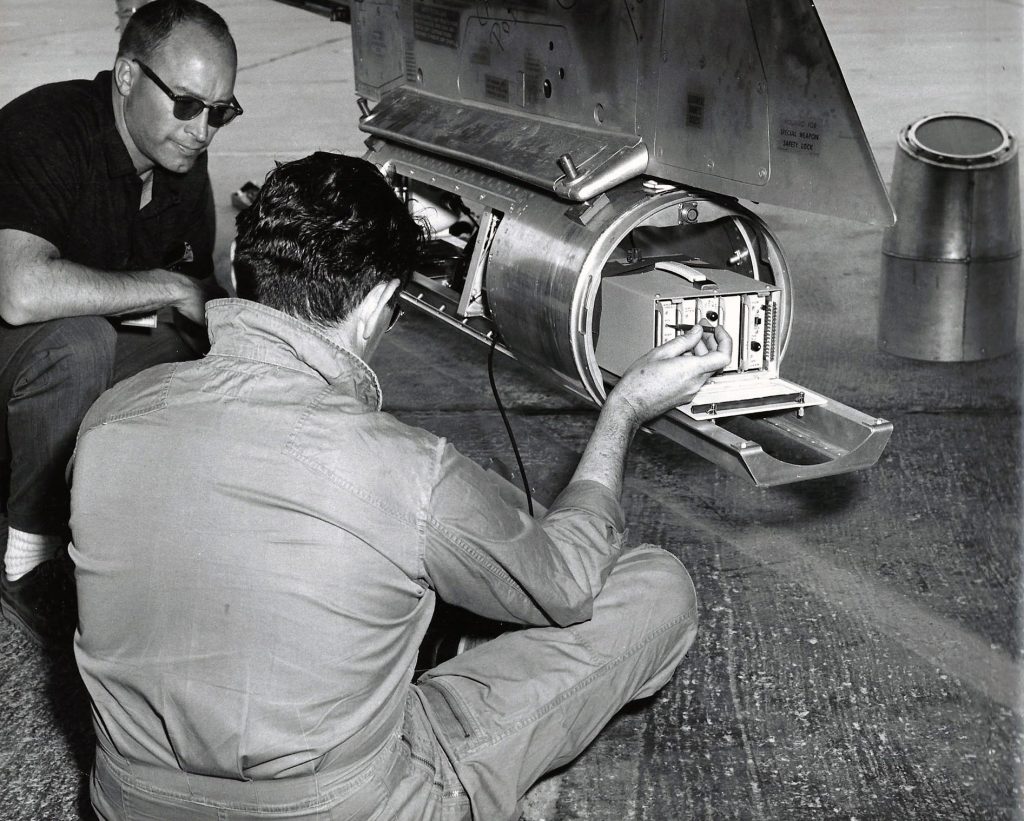

Each Phantom carried cameras housed in pod enclosures located under the wings. One pod carries a high-speed 35mm motion picture camera equipped with a 32-inch telescopic lens. The other houses a 16mm camera and television camera, both looking through a single 24-inch telephoto lens. The TV camera is linked to a monitor in the cockpit and serves as a view finder for the motion picture cameras. All focusing, exposures and other adjustments are made before flight; the pilot’s main responsibility is to keep the fast-traveling subject in the cockpit viewfinder.

Developed by APCS

The camera-bearing pods are a development of the Air Photograph and Charting Service (APCS) of the Military Air Transport Service. The system was developed by George D. Wood of APCS and Capt. James Kidder, who is assigned to the Department of Defense Manned Spacecraft Support Office.

Previous to the Gemini flight, an F-4C Phantom had employed the system on Nov. 30 to obtain color movies of the ascent of the Mariner 4 satellite and its booster rocket.

Footage thus obtained provides new and important knowledge on the behavior of boosters and spacecraft during the critical phases of launch. The horizontal view of an ascending vehicle as acquired by chase plane cameras could be much more informative than the tail view obtained by ground-based camera, which had batteries for hearts, cameras for eyes, sequencers and timers for brains and nerves. The crewman simulators, also made by McDonnell, occupied pallets where the astronauts would normally sit.

Astronauts Happy

Twelve astronauts watched the launch and followed the progress of the flight from the Flight Control Center at the Cape. These included Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom and John W. Young who are scheduled to make the first manned Gemini flight.

Said Grissom, usually a man of few words, to newsmen: “There are a lot of happy people here today. But I doubt anyone is happier than John and I. We now see the road clear to our flight and we’re looking forward to it. I’m so happy, I don’t mind appearing before you today.”

Young, asked for a comment, was brief: “I agree with everything Gus said.”

I first met Doug in the summer of 1965 upon being assigned to Lookout Mountain Air Force Station as a Producer Director. Doug was in charge of the motion picture camera department.

Since I was also a fighter pilot and still on flight status, that eventually led to Doug and I being assigned the project of improving gun camera photography. The problem was, there were no gun cameras in the F-4, the front-line fighter in the Vietnam War. The designers of that aircraft didn’t even put a gun in it. The current wisdom was that old-fashioned dog fighting was passé’ and rockets and missiles were the way to fight a war.

The interim solution was to hang an external pod containing a gun and ammunition on the centerline of the F-4 and adapt the heads-up instrumentation display to serve as a gun sight. It left a lot to be desired in accuracy and produced sporadic results, plus there was no provision for a gun camera to record the action. Doug and I went to Nellis AFB, Las Vegas, Nevada to work on the problem. We designed a jury-rigged system to cram a gun camera with a lens and a prism to shoot through the windscreen. To power the camera we had to take a bulb out of one of the cockpit lights and use that socket to plug the camera in. I ran tests on the gunnery range to select the lens focal length and color film to use for best results.

Doug was then dispatched to Vietnam and Thailand with the cameras we had available to install in aircraft designated by the Wing Commander of the various bases. Doug told about getting to Ubon AFB, Thailand and the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, dubbed “The Wolfpack”, commanded by WW II fighter Ace, Colonel Robin Olds. Olds told Doug he wanted one of those cameras in his ship by 0800 the next morning. Doug said he was fresh out of cameras but was expecting more to catch up with him the next day. Olds repeated, “Did you hear me? I want one of those cameras in my ship and it better be there by 0800 tomorrow!”

Well, Doug got on the phone and called back to Hal Albert at AAVS HQ and explained the problem. Somehow or other, a camera was absconded from another base and got to Ubon in the wee hours of the morning. Doug went to work and about 0730 Colonel Olds came striding out to man his aircraft. Doug was up in the cockpit working and saw him coming and before Olds could say anything, Doug called out, showed him the bulb he had just taken out and said, I had to rob one of your cockpit lights, but your camera will work as soon as I can get it plugged in. Olds just shook his head and tried to stifle a grin. He and Olds shared a couple of drinks in the bar that night. There were no MiGs to shoot at that day but if there had been, a gun camera would have recorded it.

Another incident occurred at Takhli AFB in Thailand where Capt Roger Mitchell was the Photo Detachment Commander. The wing there had F-105 aircraft which had rudimentary gun cameras which were seldom used. Their primary mission was dropping bombs. To record bomb impacts, Doug and I had developed a rear facing strike camera mounted externally on the wing. It was rigged to begin running at bomb release and several seconds more to allow time for the bomb to fall and explode.

Roger had received a message from his Hq, who were passing on gripes from HQ USAF that they weren’t getting good enough combat documentation from the strike cameras mounted on F-105’s at Takhli. The pilots were jinking their aircraft around after coming off the target and bomb impacts were seldom being recorded. So, Roger dutifully went to the Wing Commander, Colonel Jack Broughton and told him what Hq USAF had requested. Well, the Colonel blew his stack at Roger, (who was not a pilot), in a classic, “Ignore the Message – Kill the Messenger” scenario. He said, “You don’t know what the Hell you are talking about, Captain. Get off my base!” Doug happened to still be somewhere in the theatre installing gun cameras in F-4’s and Hal Albert asked him to get to Takhli ASAP and try to smooth things over.

So, the next morning Doug appeared in Col. Broughton’s office. He had his suitcase with him and set it down before introducing himself to the Colonel. He tried to explain to the Colonel that the Combat Photo Detachment was only trying to satisfy the Pentagon who was constantly on them for more and better combat documentation, while at the same time being mindful of the dangers that he and his pilots were facing. And he said, “Just in case you want to kick me off your base, I brought my suitcase with me – but are you really going to kick that nice young Captain out for just trying to do his job?”

Well, Colonel Broughton shook his head at Doug and the suitcase and said, “Oh Hell. I had just come off another very frustrating mission dictated by those idiots back in Washington D.C. I shouldn’t have taken it out on that Captain.” Doug then had a friendly discussion with him about the whole combat documentation business and how important it was for justifying the entire war effort. The Administration, the Defense Department and the public at large had an insatiable appetite for war footage in this new age of near real-time communications.

Captain Mitchell kept his job and the combat documentation footage coming out of Tahkli showed some improvement. It’s tough to be counting one-thousand-one, one-thousand-two, when you are being shot at and trying to be killed by those you have just bombed. However, some of the pilots at least tried to time their jinking so that when the computed time of impact elapsed, their strike camera was pointed somewhere near the target.

He eventually was instrumental in developing a blister that housed a camera and became an integral part of the fighter aircraft. For this he was awarded the Air Force’s highest civilian award, the Exceptional Civilian Service Award.

Page 6. CHANTICLEER —Friday, August 4, 1968

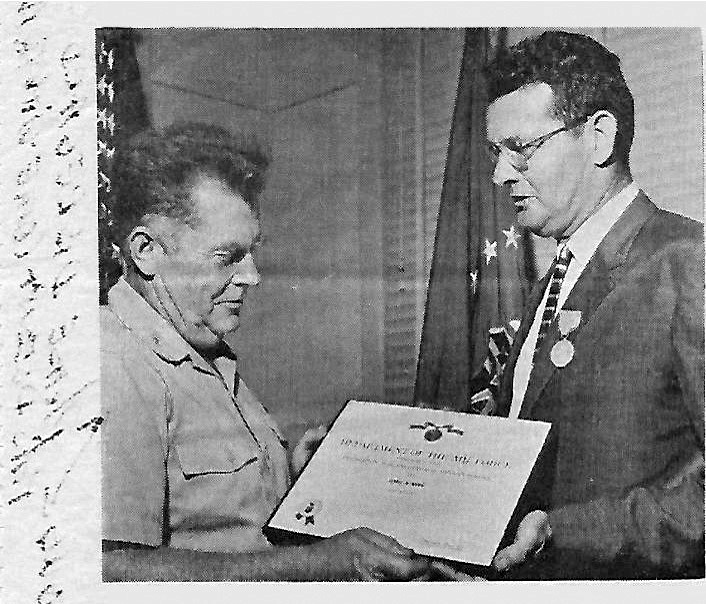

George D. Wood (r) chief, camera division for Aerospace Audio-Visual

Service’s 1352d Photographic Group, Lookout Mountain AFS, California,

receives the Air Force Exceptional Service Award from AAVS Commander,

Col. William S. Barksdale Jr.

AAVS Camera Chief Gets

Top AF Civilian Honor

An Aerospace Audiovisual Service employee from the 1352d Photographic Group, Lookout Mountain AFS, California, has received the Air Force Exceptional Service Award. George D. Wood, chief, camera division, was presented the award at Hq.

AAVS Orlando AFB by Col. William S. Barksdale Jr., AAVS commander. The award is the highest bestowed by the Air Force to a civilian employee.

Mr. Wood was cited for his development of a camera mounting development on jet fighters in Vietnam. The mount, called a camera blister holds a motion picture camera in a bubble type blister on the bottom of aircraft. With blisters mounted in both directions, targets can be recorded before and during an attack by the fighters. Valuable motion picture footage is gained daily by these cameras in air strikes against the enemy.

He continued as Chief of Motion Picture Dept after Lookout Mt. closed and AAVS consolidated at Norton AFB. He retired from AAVS in 1977.

He continued to be active with film making, including filming a logging operation on Lake Coeur d’Elene near some property he and his good friend Hal Albert owned. Later he and his son, Terry operated a U-Pick-Em used car parts operation in the high desert near Victorville, CA.

Along with some friends he was featured in the Steven Spielberg/Tom Hank film, “Shooting War”, a 2000 documentary on WWII photographers in action in Europe and the Pacific.

He was diagnosed and treated for esophageal cancer in 1995. He passed in 2009 from kidney failure related to the chemo he received for the cancer.

He was a truly remarkable man and a cherished friend.

Very cool Ken!! I never knew who developed the AAVS type IV camera pods! I was taken back to my days of hanging them when I saw the pic of the pod in your tribute!

Quite a life and quite a story! Thanks for posting this.